In honor of the birth of Sir Winston Churchill (November 30, 1874): his favorite, Pol Roger Champagne.

Food writing can't help but seem unserious in an age when serious things are afoot, that is to say in any age. You remember how we discussed whether it might not be a civilizational divide: Lin Yutang, My Country and My People (1935), noticed that in China it has always been normal for scholars, poets, and generals to write books about food, a sign of maturity he thinks, whereas in the West cookery writing has been considered "worthy of Aunt Susan only ... there is no such thing as a Galsworthy cutlet [John Galsworthy published The Forsyte Saga in 1922]." It is a nice problem. Does effetely thinking about food siphon off energies that should go to worthier matters?

Food, the arts, seriousness, is on my mind today because I happen to be enjoying the (re-)acquaintance of two long-dead but great artists. One is Maria Callas, again, seen through some YouTube videos. (Is her French as fluent as it sounds? Brava for being able to understand the five men interlocutors surrounding her couch on a Parisian talk show set in the '60s, but when she says things like "je suis libre parce que je ne fais pas les concessions" [I am free because I do not make concessions] I wonder if Madame, my French language professor, would not sniff patiently. "You are speaking English." Still, I love the fact that Callas' French interviewers quickly get to asking about the state of her soul, whereas the English Lord Harewood seems to stick to musicality and to follow the prima donna's lead. Like so -- the French -- Q: But when you speak of the duty to justify your place in life by the greatest and most perfect effort possible, it sounds as though there is another woman inside you, hectoring you. Do you not feel resentment? A: Mais non, c'est l'amour! Then, in The Callas Conversations -- Callas begins: "Of course, singing Wagner is much easier than singing Donizetti." Lord H.: "In some ways, yes." Callas (a swift look): "In every way."

The other artist in my life now is the Czech writer, gourmand, and musician Joseph Wechsberg, whose book Blue Trout and Black Truffles (1953), among others, I have long been aware of but had never yet read. Both these people, the prima donna and the epicure, either began their careers in, or drew material for their art from, serious places not exactly awash in the twentieth century's scant helpings of safety or good fortune. Callas matured in Greece just before World War II, Wechsberg in the former Czechoslovakia and in the great capitals of eastern Europe as they fell under the twin jackboots of that war and socialist control afterward. In both situations, I can't help but startle, a little, though I fear it marks me as an innocent barbarian. Like so -- what business had Athens under storm clouds to run royal opera companies for young Maria Kalogeropoulos to debut in? As for her later roles in Verona in 1947, was Italy not then busy doing serious things, "rebuilding"? Then there is this quote, from Wechsberg's essay "A Balatoni Fogas to Start With." It is all about the Hungarian restaurateur Charles Gundel, "ranked by connoisseurs all over the world in a class with Escoffier and Fernand Point." **

Some restaurants on the European continent still carry on [circa 1950] along the lines of the highest gastronomical tradition, but practically not one of them is located in the vast, bleak area behind the Iron Curtain. No meal can be perfect if the ingredients that go into it aren't, and in the countries under Soviet domination it is impossible to obtain perfect ingredients. Often it is impossible to obtain any ingredients at all. People in Czechoslovakia, Poland, Rumania and Hungary liked to eat well; the best restaurants in Prague, Warsaw, Bucharest, and Budapest ran a close second to the best restaurants in France. But now food is rationed in all these places. It is no longer a question of getting good food, but of getting any food at all.People in Poland and Rumania liked to eat well. What a thought. Yes, I suppose being human they would, just as people in Athens even under storm clouds -- developing into Axis occupation no less -- and in Verona rebuilding, liked to go to the opera.

Note how such pleasurable things come to a crashing halt when people who want to rule daily life for everyone's good take over. Especially the food part. Apparatchiks seem able to maintain a state opera company or a traditional imperial circus if it is a question of displaying national pride, but good eating and drinking is such a private, everyday thing. It relies so on the individual's creativity if he is the chef, and on his freedom to go out to eat where and when he likes, to pursue his own tastes, if he is the customer. Both need the freedom to buy and sell unhindered by equality police or nutrition police or by Economic Police. Wechsberg says these latter did exist in Charles Gundel's Budapest. They controlled the prices he could charge for meals, and visited his restaurant to spy on which guests were spending unfair amounts of money. Naturally, because some animals are always more equal than others, it ended up being just these apparatchiks, as well as the black marketeers, who could afford to patronize what few good restaurants survived in mid-20th century eastern Europe. Not that state flunkies had any interest in what they were eating. And all this is not to speak of the efforts everyone had to make to "get any food at all." Wechsberg closes this essay:

Last year, Gundel's restaurants were nationalized. Now Hungary's Communist commissars entertain their honored guests at Gundel's. The name has remained, but nothing else has. The food is bad. Gundel himself was permitted to leave. He lives in quiet retirement somewhere in Austria.He was permitted to leave. Though food writing may seem unserious in a serious world, reading Joseph Wechsberg made me suddenly reflect otherwise. Deeply unpleasant people, committed you would think to far loftier ideals than belly-filling, can nevertheless affect so basic a thing as what food there is around. We in the West have mostly been spared the fury of these scold-scourges. The only one who comes to mind as active today is the current President's wife. Perhaps the mayor of New York, too. Fortunately we are free enough to disobey the former, and even to laugh. Disobeying the latter is more problematic.

So in a way, worried about seriousness and food, we come full circle and meet a startling truth. Perhaps a perfectly good defense against the deeply unpleasant types -- assuming we do not actually have to go to war with them, in obedience to Churchill's dictum that civilization requires we "show ourselves possessed of a constabulary power before which barbaric and atavistic forces will stand in awe" -- is to record, savor, develop, and resurrect all those roasts and "ragoos." attention to which seems frivolous, but is not because everyone must eat; and because barbaric and atavistic forces will gladly progress from the control of ragoos to the control of bread and water if they can. And they always exempt themselves.

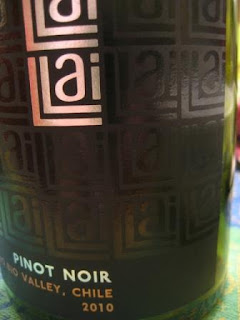

Now we began with Maria Callas, but have not talked much about her because as a Western woman pursuing her career in the West, she was free. "Libre." No equality police hounded her, insisting she sing less well. However, we're glad to discover she seems to have been a gourmande herself. Almost ten years ago, The Guardian ran a feature on her passion for food and for collecting wonderful recipes that she savored only vicariously, out of concern to manage her weight. "Tomato omelettes, veal l'orientale, sauces, cakes, and chocolate beignets" all went into her handbag in the form of scribbled notes on paper, often from restaurants. Then they found their way to her chef and her dinner parties. Guests indulged while she ate a few morsels and drank a little champagne. It's said to be less caloric than still wine. We hope that she and Aristotle Onassis (the rat) offered Churchill his Pol Roger when they entertained him on Onassis' yacht. There's an old video of the great man being helped into a tender (I think it's called? a small boat that brings people to a big boat) and giving his V for victory sign as he tootles off with his hosts. Never surrender.

** Strangely enough, John Galsworthy, he whom Lin Yutang thought would never name a cutlet, seems to have known of Gundel's. Joseph Wechsberg records that Gundel himself showed him a poem which the author of Forsyte wrote in the restaurant's guestbook one night in the 1920s, after a fine meal. It is called simply "The Prayer," and was published in Verses Old and New in 1926.

If on a spring night I went by

And God were standing there,

What is the prayer that I would cry

To Him? This is the prayer.

O Lord of courage grave,

O master of this night of spring,

Make firm in me a heart too brave

To ask Thee anything!