We are still climbing through the Purgatorio, and look what we find. Marvelous imagery, like the ladies dressed in white, green, and red (faith, hope, and love) dancing beside the right wheel of the chariot (the Church), while their four companions dressed in purple (the natural virtues, prudence, courage, justice, and moderation) dance beside the left (cantoXXIX). We find Dante, even amidst his astronomical time stamps and his inquiring of who is who among the souls purging their sins, still also interested in his own competitive place in the literature of his day. Thus in canto XXVI we meet Guido Guinizelli (ca. 1230-1276), judge, lawyer, and poet, of whom not Dante but the Notes (by David Higgins) explain,

the placing of Guinizelli here in Purgatory, on the cornice of the promiscuous, must reflect something of Dante’s sense of having superseded Guinizelli himself both in the range of his poetry and the concept of love that inspires it. In Dante’s concept, free of all the deterministic and therefore earthly elements still detectable in Guinizelli, the highest love is intellectual, entirely transcending the flesh.

It would be as if I wrote a Divine Comedy today and put in Purgatory bloggers whom I think I have superseded. And yet if I were Dante I would be considered, I would be, a very great artist and a gigantically morally mature human being, and so my decisions would be regarded seven hundred years later as correct and fascinating. I alone would give any fame, for example, to the Provencal troubadour Giraut de Bornelh (1150-1220), and I would place speech in the mouth of another, Arnaut Daniel, in his own Provencal language in the middle of all my Tuscan terza rima. “A striking demonstration (as was intended) of Dante’s linguistic virtuosity as well as a tribute to Arnaut and the whole corpus and ethos of Provencal lyric poetry.”

And then we find, again among the Notes, Dante given credit for a change to Western literature which you the reader would have passed by without a blink, just on your own. I did. Take a look.

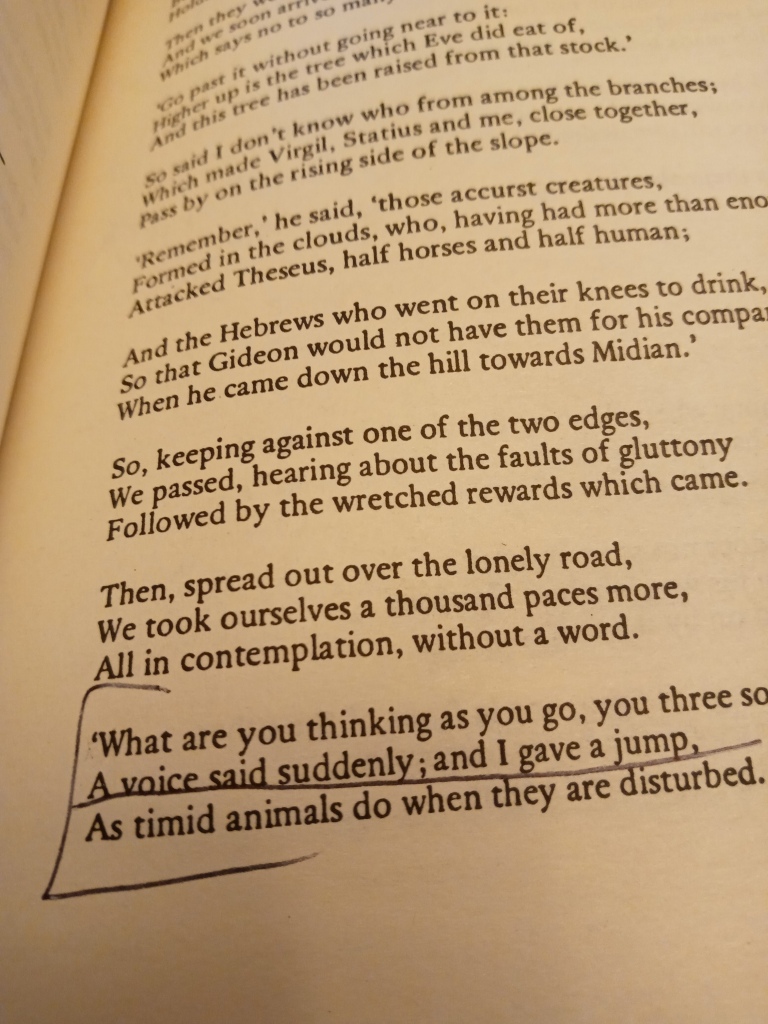

This is “a new realism and conception of scene in Western literature,” evidently because here a careful, professional craftsman’s balance, or a sort of mythological minuet of narration and symbolism, is interrupted by a new person saying something unexpected. In fact, demanding attention for himself. As will happen in life. “What are you thinking as you go?” I gave a jump. It is the Angel of Temperance who has stopped the action, in what the movies call a jump cut, to tell the climbers about a safe and easy turn up the mountain. They could have found it in the more usual, programmed way. Dante’s imagination went elsewhere, and ever after, ours does too. The Angel’s appearance by the way reminds me of what the children of Fatima reported about the look of souls in hell, at once fiery, black, and transparent: “never, even in a furnace, appeared/ Glass and metal so shining and so glowing/ As I saw the one who said, ‘If it should please you to go up/ You had better turn here’ ” (Canto XXIV).

I don’t know whether my translation of the Divine Comedy, by C.H. Sisson, is considered very great. Having reached Purgatorio XXXI, I look back and find that it is staying rather infelicitous, chilly somehow. A good article at The American Scholar reports that of all people, who should have written “one of the first complete and in many respects the best” English translation but our own Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1867). Who knew Longfellow was a professor of Italian at Harvard? Coping with Dante’s “intensely idiomatic, rhyme-rich Tuscan [and its] surging terza rima meter that gives the poem its galloping energy—a unique rhythm that’s difficult to reproduce in rhyme-poor English” — is everybody’s problem. John Ciardi, Allen Mandelbaum, Dorothy Sayers. Rhyme-poor English, yes, for everyone, but what’s missing from Sisson is also galloping energy. An English poem that enshrines both happens to be Longfellow’s own The Song of Hiawatha. I read this straight through at about the age of thirteen, before ever hearing anybody make fun of its Gitchee-Gumee cadences. I entirely enjoyed it. I was quite proud of recognizing the poet’s hidden way of describing corn, as a slim green goddess with her waving silken crown.

Anyway we are on our way, up to the top of the mountain of Purgatory and almost to the Paradiso. Virgil has left, almost without notice, as can happen in life. “But Virgil had taken himself away from us/ Virgil my sweetest father” (canto XXX). As consolation we have met the lovely, as yet unnamed girl, who walks along the river opposite Dante and serves to represent the active life, as the Biblical Leah did in Dante’s dream just before. If you are a teacher and want to find out if your students are really reading this thing, ask about Matilda.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for stopping by ...